An Interview With

IRVING and DOROTHY

CROWELL

An Oral History conducted and edited by

Robert D. McCracken

Nye County Town History Project

Nye County, Nevada

Tonopah

1987

COPYRIGHT 1990

Nye County Town History Project

Nye County Commissioners

Tonopah, Nevada

89049

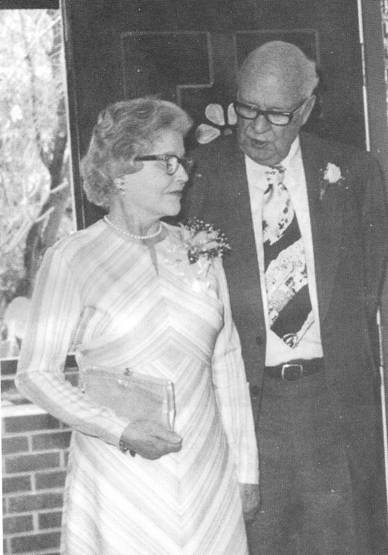

Irving and Dorothy Crowell

1976

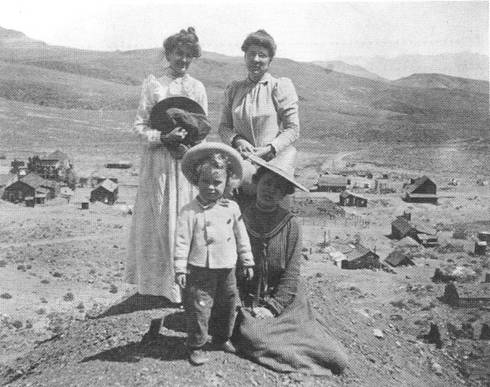

The child pictured here is J. Irving Crowell, Jr., about 1903, Candelaria, Nevada.

CONTENTS

Remarks on the elder J. Irving Crowell; J.I.'s schooling; J. Irving's railroad accident forces J. I. to leave Stanford; J. I.'s memories of summers helping J. Irving at Chloride Cliff; early railroads.

Working in Los Angeles; returning to Beatty to re-open the fluorspar mine.

Dorothy and her mother visit Beatty; first impressions; the floods of 1969 and 1923; raising children in Beatty; health care; the three-day drive to Los Angeles; later travels.

The Nye County Town History Project (NCTHP) engages in interviewing people who can provide firsthand descriptions of the individuals, events, and places that give history its substance. The products of this research are the tapes of the interviews and their transcriptions.

In themselves, oral history interviews are not history. However, they often contain valuable primary source material, as useful in the process of historiography as the written sources to which historians have customarily turned. Verifying the accuracy of all of the statements made in the course of an interview would require more time and money than the NCTHP's operating budget permits. The program can vouch that the statements were made, but it cannot attest that they are free of error. Accordingly, oral histories should be read with the same prudence that the reader exercises when consulting government records, newspaper accounts, diaries, and other sources of historical information.

It is the policy of the NCTHP to produce transcripts that are as close to verbatim as possible, but some alteration of the text is generally both unavoidable and desirable. When human speech is captured in print the result can be a morass of tangled syntax, false starts, and incomplete sentences, sometimes verging on incoherency. The type font contains no symbols for the physical gestures and the diverse vocal modulations that are integral parts of communication through speech. Experience shows that totally verbatim transcripts are often largely unreadable and therefore a waste of the resources expended in their production. While keeping alterations to a minimum the NCTHP will, in preparing a text:

a. generally delete false starts, redundancies and the uhs, ahs and other noises with which speech is often sprinkled;

b. occasionally compress language that would be confusing to the reader in unaltered form;

c. rarely shift a portion of a transcript to place it in its proper context;

d. enclose in [brackets] explanatory information or words that were not uttered but have been added to render the text intelligible; and

e. make every effort to correctly spell the names of all individuals and places, recognizing that an occasional word may be misspelled because no authoritative source on its correct spelling was found.

As project director, I would like to express my deep appreciation to those who participated in the Nye County Town History Project (NCTHP). It was an honor and a privilege to have the opportunity to obtain oral histories from so many wonderful individuals. I was welcomed into many homes—in many cases as a stranger--and was allowed to share in the recollection of local history. In a number of cases I had the opportunity to interview Nye County residents when I have known and admired since I was a teenager; these experiences were especially gratifying. I thank the residents throughout Nye County and southern Nevada--too numerous to mention by name--who provided assistance, information, and photographs. They helped make the successful completion of this project possible.

Appreciation goes to Chairman Joe S. Garcia, Jr., Robert N. "Bobby" Revert, and Patricia S. Mankins, the Nye County commissioners who initiated this project. Mr. Garcia and Mr. Revert, in particular, showed deep interest and unyielding support for the project from its inception. Thanks also go to current commissioners Richard L. Carver and Barbara J. Raper, who have since joined Mr. Revert on the board and who have continued the project with enthusiastic support. Stephen T. Bradhurst, Jr., planning consultant for Nye County, gave unwavering support and advocacy of the project within Nye County and before the State of Nevada Nuclear Waste Project Office and the United States Department of Energy; both entities provided funds for this project. Thanks are also extended to Mr. Bradhurst for his advice and input regarding the conduct of the research and for constantly serving as a sounding board when methodological problems were worked out. This project would never have became a reality without the enthusiastic support of the Nye County commissioners and Mr. Bradhurst.

Jean Charney served as administrative assistant, editor, indexer, and typist throughout the project; her services have been indispensable. Louise Terrell provided considerable assistance in transcribing many of the oral histories; Barbara Douglass also transcribed a number of interviews. Transcribing, typing, editing, and indexing were provided at various times by Alice Levine, Jodie Hanson, Mike Green, and Cynthia Tremblay. Jared Charney contributed essential word processing skills. Maire Hayes, Michelle Starika, Anita Coryell, Michelle Welsh, Lindsay Schumacher, and Jodie Hanson shouldered the herculean task of proofreading the oral histories. Gretchen Loeffler and Bambi McCracken assisted in numerous secretarial and clerical duties. Phillip Earl of the Nevada Historical Society contributed valuable support and criticism throughout the project, and Tam King at the Oral History Program of the University of Nevada at Reno served as a consulting oral historian. Much deserved thanks are extended to all these persons.

All material for the NCTHP was prepared with the support of the U.S. Department of Energy, Grant No. DE-FG08-89NV10820. However, any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of DOE.

--Robert D. McCracken

Tonopah, Nevada

June 1990

Historians generally consider the year 1890 as the end of the American frontier. By then, most of the western United States had been settled, ranches and farms developed, communities established, and roads and railroads constructed. The mining boomtowns, based on the lure of overnight riches from newly developed lodes, were but a memory.

Although Nevada was granted statehood in 1864, examination of any map of the state from the late 1800s shows that while much of the state was mapped and its geographical features named, a vast region--stretching from Belmont south to the Las Vegas meadows, comprising most of Nye County--remained largely unsettled and unmapped. In 1890 most of southcentral Nevada remained very much a frontier, and it continued to be for at least another twenty years.

The great mining booms at Tonopah (1900), Goldfield (1902), and Rhyolite (1904) represent the last major flowering of what might be called the Old West in the United States. Consequently, southcentral Nevada, notably Nye County, remains close to the American frontier; closer, perhaps, than any other region of the American West. In a real sense, a significant part of the frontier can still be found in southcentral Nevada. It exists in the attitudes, values, lifestyles, and memories of area residents. The frontier-like character of the area also is visible in the relatively undisturbed quality of the natural environment, most of it essentially untouched by human hands.

A survey of written sources on southcentral Nevada's history reveals same material from the boomtown period from 1900 to about 1915, but very little on the area after around 1920. The volume of available sources varies from town to town: A fair amount of literature, for instance, can be found covering Tonopah's first two decades of existence, and the town has had a newspaper continuously since its first year. In contrast, relatively little is known about the early days of Gabbs, Round Mountain, Manhattan, Beatty, Amargosa Valley, and Pahrump. Gabbs's only newspaper was published intermittently between 1974 and 1976. Round Mountain's only newspaper, the Round Mountain Nugget, was published between 1906 and 1910. Manhattan had newspaper coverage for most of the years between 1906 and 1922. Amargosa Valley has never had a newspaper; Beatty's independent paper folded in 1912. Pahrump's first newspaper did not appear until 1971. All six communities received only spotty coverage in the newspapers of other communities after their own papers folded, although Beatty was served by the Beatty Bulletin, which was published as a supplement to the Goldfield News between 1947 and 1956. Consequently, most information on the history of southcentral Nevada after 1920 is stored in the memories of individuals who are still living.

Aware of Nye County's close ties to our nation's frontier past, and recognizing that few written sources on local history are available, especially after about 1920, the Nye County Commissioners initiated the Nye County Town History Project (NCTHP). The NCTHP represents an effort to systematically collect and preserve information on the history of Nye County. The centerpiece of the NCTHP is a large set of interviews conducted with individuals who had knowledge of local history. Each interview was recorded, transcribed, and then edited lightly to preserve the language and speech patterns of those interviewed. All oral history interviews have been printed on acid-free paper and bound and archived in Nye County libraries, Special Collections in the James R. Dickinson Library at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and at other archival sites located throughout Nevada. The interviews vary in length and detail, but together they form a never-before-available composite picture of each community's life and development. The collection of interviews for each community can be compared to a bouquet: Each flower in the bouquet is unique--same are large, others are small-- yet each adds to the total image. In sum, the interviews provide a composite view of community and county history, revealing the flow of life and events for a part of Nevada that has heretofore been largely neglected by historians.

Collection of the oral histories has been accompanied by the assembling of a set of photographs depicting each community's history. These pictures have been obtained from participants in the oral history interviews and other present and past Nye County residents. In all, more than 700 photos have been collected and carefully identified. Complete sets of the photographs have been archived along with the oral histories.

On the basis of the oral interviews as well as existing written sources, histories have been prepared for the major communities in Nye County. These histories also have been archived.

The town history project is one component of a Nye County program to determine the socioeconomic impacts of a federal proposal to build and operate a nuclear waste repository in southcentral Nye County. The repository, which would be located inside a mountain (Yucca Mountain), would be the nation's first, and possibly only, permanent disposal site for high-level radioactive waste. The Nye County Board of County Commissioners initiated the NCTHP in 1987 in order to collect information on the origin, history, traditions, and quality of life of Nye County communities that may be impacted by a repository. If the repository is constructed, it will remain a source of interest for hundreds, possibly thousands, of years to come, and future generations will likely want to know more about the people who once resided near the site. In the event that government policy changes and a high-level nuclear waste repository is not constructed in Nye County, material compiled by the NCTHP will remain for the use and enjoyment of all.

--R.D.M.

CHAPTER ONE

RM: J.I., why don't you tell me when and where you were born.

JC: I was born in Los Angeles, December 14, 1900.

RM: Who were your parents and what were their backgrounds?

JC: J. Irving Crowell and Annie L. Crowell. My father was an Easterner from Cape Cod. Mother was a Canadian, from Prince Edward Island. My father came out here and purchased the Chloride Cliff claims from Kimball and 2 other people in the early 1900's.

PM: Before 1905, before Bullfrog and Rhyolite, or after?

JC: About the same time. Because there were no railroads in here, he had to come here by going to Vegas and coming up by team--3 days to get to Rhyolite. Of course, in those days everything centered around Rhyolite, not Beatty.

RM: How, did your father wind up here?

JC: Well, basically, much as I hate to say it, Dad was a promoter, and everything that he tried to promote finally made money, although he wasn't in on the making of all of it. Chloride Cliff made money, but not for him--for the leasers out there. Well, more or less, he came in here [to Beatty], I think, on the spar, the fluorspar, which is calcium fluoride.

RM: And what is it used for?

JC: Well, it's really a catalyst. It never enters into a chemical reaction, but it really promotes fluidity to anything that is added to it. Now, its main use has been in steel. They use it to thin their slag. It doesn't enter into it, but it thins it so that the slag will run off instead of getting thick and pasty. Of course at the present time the steel is all gone. Our customers now are mainly cement companies.

RM: Now, Dorothy, why don't you tell me where you were born and when and just a few words about your folks.

DC: I was born in Los Angeles, California, on August 2, 1904. My father owned a bakery there for quite a few years. I grew up there. There isn't very much to tell. I was an ordinary gal. I never made it to college; I wanted to be a kindergarten teacher. I love little kids. My mother died of tuberculosis when I was 6 years old, and I lived with his parents. My grandparents were wonderful to me, and his sister, Gertrude McDowell, became my mother. She was just so dear to me, and I couldn't have been happier, I guess, probably had my own mother lived. There isn't much to tell. I wanted to be a kindergarten teacher since I've always loved kids. That was my wish, but my darling aunt was not too well. She died of cancer. She just wasn't able to put me through 2 years. It would have taken 2 years of college to become a kindergarten teacher, but I never did make it.

RM: Well, Irving, you say your father arrived here by team from Is Vegas. Did he immediately go to the Chloride Cliff property?

JC: Yes. He tried to promote that. Well, just like all promoters, at one time you're high on the hog, and the next time you wonder where your next meal is coming from.

RM: Did he live out there on the property, or did he live in Rhyolite?

JC: No, he lived right on Chloride Cliff.

RM: How long did he work on the Chloride Cliff operation?

JC: Well, I would say from about 1905 until about 1917 when he moved in here.

RM: I see. You said that as a youth you came out from Los Angeles in the summers. Could you tell us about that?

JC: I went to public school in Los Angeles until just the beginning of high school. Dad was in the chips, as you might say, and he enrolled me in San Diego Army/Navy Academy at Pacific Beach, down by San Diego. I stayed there 3 years and then things weren't going too good financially, so I had to came back to Los Angeles and graduated from Polytechnic High School there. Things got going better--as they always seemed to--and I enrolled in Stanford in the class of '24, and I was there for 3 years, and then the beginning of the 4th year we had financial reverses again.

DC: Poor Dad!

JC: Yes. I had to give up college at Stanford. I started in at U.C.L.A. because we couldn't afford that tuition. So, I started there, and then in October Dad was in a railroad accident.

My father was going in a Pullman car from here. The T&T went down to Ludlow and then dropped the Pullman, and a train on the Santa Fe came along and picked it up. Well, the Pullman car came loose, way out on the main line. They backed up and the engineer thought he was going clear back to Ludlow, but he hit the car, the railroad says, at 35 miles per hour. Well, of course that should have put my father in the hospital, but he wouldn't go. From then on, he was an invalid. That was the end of his coming out here.

RM: What year was that?

JC: Oh boy, you know it's hard to pin down years like that. Oh, well, this was when I had to leave school. That was '23 or '24. My class in Stanford was '24, and it would have been the same in U.C.L.A. That was the end of schooling and I came out here.

RM: Did he have to stay in L.A. from then on? Was he literally bedfast?

JC: Yes, he was for months. And he got the terrific sum of $7,000 from the railroad, the Santa Fe. It was the Santa Fe that dropped it. But I tried to run the mine as he would.

RM: This was the Chloride Cliff?

JC: No, this. In 1917 we moved in here to the fluorspar.

RM: Yes, I follow you now.

JC: I tried to run it, and of course it wouldn't work. And then things got from bad to worse and it ended up, with Dad paying off all the bills, but he did have a title to the fluorspar property clear.

RM: Was it a patented claim?

JC: No. They're unpatented.

RM: Tell me about how they found it and acquired the fluorspar property, and tell us exactly where it is.

JC: Well, it's located 5 miles due east, a little bit south of east of Beatty. It was known in the boom days of Rhyolite as the Lige Harris.

RM: That was the name of it?

JC: Lige Harris, but it was pronounced "large." But he knew, of the value of it; he knew the fluorspar because in those days miners found fluorspar and followed it down, and it led them into gold. And then one of the men working for him, Bill Kennedy, found fluorspar. Be threw a pick off his shoulder and just turned up a little purple. Course the next morning, why, Bill Kennedy told Dad that he'd found the fluorspar mine. Dad looked at it and bought it from him right then and there.

RM: Do you remember how much he paid and how many claims there were?

JC: Yes. $500. This was just the one claim. Dad built on it and he never even located it. I told Dad about it, and Dad looked at it, and it was purple. Who took the chance?

RM: Yes. Sure.

JC: And then, oh, 4 or 5 months after that, why, this Bill Kennedy did the same thing again. $500.

RM: Your Dad bought another fluorspar from him? In the same area?

JC: Same area. Never amounted to anything.

RM: The second one?

JC: The second one. But, the first one, we're still working on. I don't know how many tons have been shipped. My son can give you a pretty good estimate of what has been shipped, but we've gone 5 and 6 hundred tons a month out of it and still shipping.

RM: Where do you ship it to?

JC: Well, right now we're shipping to the cement companies. There is no steel. One plant we shipped to, in Seattle, the Japs bought. Picked it up and moved it over to Tokyo. Not only the customer, but the whole thing went over.

RM: They use fluorspar in cement, don't they.

JC: Yes. They use it in anything where they want to lower the melting point. It's a catalyst.

RM: So how do you ship it out; by truck, your own truck?

JC: Well, yes, we used to have a diesel. And they'd haul it to Vegas and ship it. From the time we got an order placed, by wire, it would take about a week before we could deliver the product. We'd have to haul it down. Monolith started to haul their own spar from here.

RM: Monolith, OK. They have their own mine?

JC: No, they don't have a fluorspar mine. They buy fluorspar from us, but they sent their trucks out here to get it. We couldn't afford a truck for a portion of it, so we just gave up the trucking business and let the customer designate who was going ship it or who was going to haul it, and

then they'd come out here and we'd load it. That's worked fine.

RM: Now, you first came into the Beatty-Rhyolite area in what year?

JC: Well, until 1917 I was in Rhyolite. We moved over here and then Rhyolite just folded up.

RM: Yes, well, you first came to Rhyolite in 1909 or '10, didn't you say. Can you tell me your recollections of what Rhyolite was like then?

JC: It was quite a town, a regular boom town. I remember Dad telling me that. I'll always remember where I had my first glass of champagne--in the Southern Hotel in Rhyolite, right across the street from the Overbury Building.

RM: What was the Southern Hotel? Was it a big hotel?

JC: No, not a modern day hotel. It was just an old-time hotel. But Rhyolite was quite a town.

RM: You were just a kid. What did the kids do for fun there?

JC: Well, I used to be at the Cliff; I wasn't allowed in town.

RM: Oh, you were working, huh?

JC: Oh, I wouldn't say working, but I was over there with than working.

RM: So, you would just come into Rhyolite to get supplies, or something?

JC: Well, you wouldn't even do that, because a teamster by the name of Al McPherson used to haul everything out with the team. I don't ever remember cars being around, just horse and buggy. It took 5 hours to get out.

RM: Five hours from Rhyolite to the Cliff. How far was it?

JC: Eighteen miles.

RM: Do you have any other recollections of Rhyolite, like any anecdotes, or impressions that stick with you?

JC: No. The only important person I knew of was McPherson, who was the teamster. But, you see, I'd just come into Rhyolite. We'd spend the night and then the next morning McPherson would take Dad and myself on out to the Cliff or, if I came without Dad, which I did a number of times, why McPherson would pick me up, then we'd pick up the supplies and go out. My father's partner, Don Findley, would walk from the Cliff down to the Keane Wonder Mine, which had a telephone. He could telephone McPherson what they wanted, and McPherson would bring it up.

RM: Did you ever get over to Beatty during this period?

JC: Oh, yes, yes.

RM: What would bring you over to Beatty?

JC: As a matter of fact, I don't remember how we got over here, but my father was looking at a mill down at Gold Center, we call it the narrows now, and going back I remember instead of waiting for a team, he flagged the LV&T. Yes, just get in the middle of the row of rails and wave your shirt over your head until you got two whistles from the engineer; then you stepped aside. Brought the car up to you, and you got on, and went on in. Some means of transportation!

RM: Any other recollections of Beatty during this very early period?

JC: No. You see everything was done through Rhyolite. I don't remember coming over to Beatty until '17 when my father moved over here. And then, of course, everything was done from here.

RM: What was Beatty like in 1917?

JC: Well, a shell of what it is now. It's grown a lot.

RM: Could you describe it?

JC: Well, how do you describe just the street. I used to say that I never expected to see a big growth through Beatty, and I firmly believed it. Everything was railroad in those days. You built a railroad to haul ore, or haul anything.

RM: Nobody thought of going by road, did they?

JC: No, indeed.

RM: Yes. Well, let's describe what Beatty looked like as you'd come in. What road was it? Did the T&T come up into Beatty or was that the LV&T?

JC: Both. They used to talk about Beatty as Chicago in the West. They had 3 railroads, see? The T&T actually terminated here. They used to back into Rhyolite, down in the lower end of it. But then, it tied in with the other railroad from here--the BG, the Bullfrog Goldfield, which went from here to Goldfield. And then, of course, the LV&T went on through.

RM: Well, did the LV&T and the T&T share the same track caning into town, right down at the gap down here?

JC: Well, no. No, the LV&T and the T&T came in on their own rails. The LV&T went on through, went in and circled the town, went out through Rhyolite, Mud Springs and on up across the flat. What is that, Sarcobatus Flats?

RM: Yes.

JC: And on up to Goldfield. That was the LV&T. The T&T also came up here, and the T&T, as such, terminated here, but then it tied in with the BG. After the LV&T was taken out--I think that was taken out in '18--the T&T, I believe operated the BG; they ran on through for quite a while. And then, of course the T&T terminated here.

RM: The station was down here where the little store is now, wasn't it?

JC: Roughly, yes, down on the other side there. It's hard to tell you exactly where it was. I think some of these movies will show that. [There was a hotel] the street diagonally from the other Reverts' station, the one that burned down. There was a hotel there. And then, of course, they had the Exchange.

RM: That was there then?

JC: Oh, yes, that's always been there just the same.

RM: During the period prior to 1917, what kept the Beatty economy going? Was it a mining center, or was it the water or what?

JC: I have no idea.

RM: What kept it going in later years - it was mining, wasn't it?

JC: Well, yes, there's been a lot of us dabbling in mining all around. But the mining, the way it used to be done, would get in and just dig out a little bit then ship it. Ten, 20-ton lots. But that was all done by the railroad.

RM: So your father acquired the fluorspar property. What did he name the mine then?

JC: Well, it is just called the Daisy Group.

RM: And he began operating that. Was that after his accident?

JC: No, that was before, because, you see, that was about 1917. The accident was in '23. Because that's when my education terminated.

RM: Yes. So there was a 6-year period in which he operated the fluorspar as his property. What all did he do with that property during these 6 years; tell me some of the things he did.

JC: Well, they sank the shaft down to, I think, 134 feet. And, as all promoters, they had to have a mill, so they put up quite a mill here. RM: Was it on the property, or here in town?

JC: No, right here in town. Matter of fact, the building is still out there.

RM: It's right here, right here in your back yard, almost.

JC: The railroad came right into it there. We had a loading ramp right there.

RM: That wasn't the main line; it was just a spur, wasn't it?

JC: No, that was the main line that went on through Rhyolite.

RM: Oh, that would have been the LV&T?

JC: That's right.

RM: What did his mill consist of, do you know?

JC: Yes. Well, concentrating tables. I put flotation in afterwards and played around with that a little bit. But, during the time that the mine and the mill was inactive, I went into steel.

RM: Now, what years were this?

JC: Well, this was about '23 or '24.

RM: After your father's accident?

JC: That's right. After I'd been out here for a while and found out that that you couldn't make it that way, why, I went back to Los Angeles. Steel has always interested me, electrometallurgical steel. So I went into that. A fellow I worked for, man by the name of Drummond, had a patented process to make grey iron out of old tin cans, and I worked for him for a number of years, well, 3 or 4 years. After I quit college I went to a rock plant, Devore, going fast, and worked there for 9 months. And then after that I went into this steel mill and this Drummond was going to help me follow that in the installation of electric furnaces.

RM: Was this in the Fontana area?

JC: Well, no. In Los Angeles, Durox Steel Company. And he made it possible for me to go down and work with U.S. Steel at Torrance. And, of course, after I got to know than pretty well, why, as they will with any kid, they let me do all the work, which I was glad to do because that's what I wanted to do. And of course the topic of conversation got around to fluorspar. Then one of the melters who was quite high up the chain said I was just a plain damn fool to work for anybody else when I had a fluorspar mine.

RM: So, you just left the fluorspar after your father's injury. Did you come up to the mine after his injury and try to work it?

JC: No, let it go. I was sort of disgusted with it. But then I got back into it through this melter, and we got to be quite friendly. As I say, he said you're a plain damn fool to work for somebody else when you have a fluorspar mine. And I said, "All right, if I care back and open that up, will you buy it?" He said, "I sure will. You can count on me." Well, I did and he did; that's the way it got started.

RM: So then, you started shipping your fluorspar to U.S. Steel at Torrance.

JC: Yes, and another man I owe an awful lot to was Arthur Swenerton of Bethlehem Steel.

RM: OK. What was the first man's name at U.S. Steel?

JC: Anderson. I couldn't get any place with their purchasing agent so I got in touch with this Anderson. I'm not sure of that name, but anyhow, I got him on the phone and explained. He said, "Leave it alone." And a couple of days after that I got the first order from U.S. Steel. And then I got in to see this Art Swenerton of Bethlehem Steel, and he found out that I was actually producing, and we struck up a friendship. I used his name as a reference, and it just built up from there. But that was the start of it.

RM: So this would've been in the '20s?

JC: This was after we were married, and we were married in '28. I came back here in '27 and opened the mine up. So it was the first part of '28.

RM: OK, yes. So then you were involved in active production in the mine from then on?

JC: Yes; I used to work up there 12 hours a day, 30 days out of the month.

RM: Were you milling your ore?

JC: No. Just shipping it raw. Because I found out that there were 2 markets. One for the 85/5, they used to call it, which was a fluxing ore; and the other, the high grade.

RM: What did the 85/5 mean?

JC: Well, 85 percent, minimum percent calcium fluoride, and 5 percent maximum silica.

RM: Yes. And then what was the other, the high grade?

JC: Well, it was supposed to be over 90 percent, but very low in silica.

RM: Were you shipping it out on the T&T at that time?

JC: That's right.

RM: What kind of technology were you using in your mine at this time? It was underground, wasn't it?

JC: Oh, yes. You see, when I took it over, the main shaft was 134 feet and there really was one level. I used to go down there. I had an old Italian that stuck with me who used to work for my father. He would work the 8 hours, and then I'd go back at night and climb down the 134 feet, load up a bucket, and climb back up, hoist it, until about 10:00 at night. But I got it done!

RM: That's getting it up there the hard way, isn't it?

JC: Yes it is, but it accomplished the job.

RM: How many miners did you have working underground?

JC: There were the 2 of us.

RM: The 2 of you broke it and then you'd go back at night and hoist it?

JC: Well, I'd hoist some during the day. He would load too. Louis Vidano was the Italian's name. He had been with my father at the Cliff for I don't know how many years.

RM: Was your father still living at this time? Or was he an invalid?

JC: Well, I brought him out here at times. But he wasn't an invalid. He could get around. But my father never could work, never manual labor, or mechanical, or anything like that. He just didn't have it.

RM: What kind of injuries did he receive in the accident?

JC: Well, he had 5 hernias, and basically that's all. But his head went through the partition between the berths. It hit that hard. I went down to meet him, actually, trying to find out what happened. I finally got up to somebody and he said, "Oh, they just hit the rear car a little hard; that's all." I said, "Yeah, but my father was in that rear car."

RM: He was the only one in it?

JC: No, there were 4 or 5 other people.

RM: Were they badly injured?

JC: Well, no. Nobody was killed. I'm not sure, but I think my father was probably 5'10" or 5'9". But he weighed around 200 pounds. And he had quite a paunch on. And of course that was the trouble. But I can't imagine hitting a car at 35!

RM: Yes. What kind of a hoist did you have on your mine at this time?

JC: We had a 15-horsepower Fairbanks-Morse, torch-ignited, an old, old engine that my father bought years ago. But it worked for us until we changed it.

RM: They didn't have jacklegs in those days, did they? What did you use to drill with?

JC: Well, fluorspar is relatively soft, so we made hand augers.

RM: I see. So you didn't have any air down in the mine.

JC: No. No air at all.

RM: And it probably didn't take much powder, did it?

JC: No, we used to get a carload per box. Well, powder costs money. We'd just put a stick or two in, and just shake it up. And all of it was picked out. Kept a good sharp pick. You got clean ore, that's all.

RM: Was your deposit in a vein or a body?

JC: Well, yes, both. Well, we've had it down to about 6 inches in width and I can show-you one place there where it was 70, 80 feet wide.

RM: Just pinches in and then bellies out, huh?

JC: And you'd never know which is going to be which.

RM: Does it go to surface?

JC: It goes to the surface. There's a lot of overburden on it.

RM: You mean, you stope it out?

JC: Yes.

RM: Then how did you get it in to the railroad?

JC: By this diesel truck.

RM: So how long did you continue on with this mining process here?

JC: We're still mining it the same way.

RM: Is it still basically a two-man operation?

JC: No. Oh, we've had 15, 20 fellows at a time. But it's a hand-sorting job. That's the only way that you can keep clean ore.

RM: Yes. You weren't affected by the war, were you?

JC: No; not negatively.

RM: They wanted more, didn't they?

JC: That is right. They were always after us. They'd say, "More, more." Natter of fact, I had a hell of a time getting that phone line in here. Well, I knew the purchasing agent of U.S. Steel in San Francisco, L. S. McCall, and he went to bat for us. Otherwise, we never would have gotten a phone.

RM: Well, would you tell me how Beatty has changed over the years from 1917 on? Start in the early years and tell me how it changed and what made it change.

JC: Well, that's a hard question to answer. Well, the AEC out here. There are a lot of people who live here that work out there. Everything used to be by the rails. You never thought of shipping anything that wasn't ready for the railroad. Like Chloride Cliff. And then lots of ore. Leasers went in. Bunches--say, 20, 25 tons of ore. During the Depression I hauled a lot of that out for them, both with a motorcycle and with a truck. At a siding down there. We had a Harley-Davidson motorcycle. Now, that was a weird thing. It had a box on the back of it. The regular sprocket was tied onto a shaft so the chain drove that shaft. The shaft went out both sides of it. And that rutted on the rubber tires. The front end of 1923 Buick. We took that out and welded it. I didn't do this; a man by the name of Sam Lafer did that at the Cliff. It would run on a 30-inch trail, so they made the trails the width of the motorcycle. It had a stinger out the back in case it stopped so you wouldn't roll it. But anyhow, something happened one time and it rolled over on Sam and crushed one of his sinus cavities. He was in pretty bad shape, but I helped him out when he was in the hospital, and ended up by buying the motorcycle and doing that myself.

RM: How much could you haul on it?

JC: Well, of the sulfides that they were getting out there, you could get about 1200 pounds. Now bear in mind sulfides are very heavy. Do you know what galena is?

RM: Sure.

JC: Well, that's what they were; mostly galena. We would haul that up to where we could get at it with a truck and then load it in a truck and haul it in to a spur down here just below Beatty.

RM: What was the name of the spur? Do you remember?

JC: I don't know. Oh, it had a name; it had to have a name. But it was down by the old Post Ranch, dawn where the Beatty airfield is now. There during the Depression we fed our family on that. One year we shipped just one 40-ton car.

RM: What did you get for fluorspar over the years? What did it bring a ton in 1917?

JC: Ah, shoot, I was selling it for $11 a ton, but I was eating.

RM: What was that, 85 and 5?

JC: It was 85/5.

RM: What did it go for in the '20s before the Depression?

JC: I think around $23. Well, $11 in the Depression is as low as we have ever sold it for.

RM: And then, what did it go for when the war was on?

JC: I don't remember. We shipped it for years at $23.

RM: What is it now?

JC: Well, we're getting 81 cents per unit. It's in the 60s.

RM: And you've still got ore in the mine, and your son is still operating the mine?

JC: Yes, that's right.

RM: What kinds of other mining operations were going on around here during this period?

JC: Well, they mine clay down here.

RM: At the Amargosa?

JC: Yes. But I also mean right down here, just over the hill.

RM: Right near Beatty. What kind of clay was it? Bentonite?

JC: You know, I can't answer that. I stick to my own. I've found that it's so much nicer if somebody asks you about it and you don't know anything about it. Well, a lot of them are fly-by-nights and trying to get somebody to put up the money. And it's much better not to give than a black eye if you say anything about them. It's so much easier that way.

RM: Dorothy, could you tell us about when you first came to Beatty?

DC: What date?

JC: Well, you and my mother came out to visit in 1927 to give you a chance to back out.

DC: To see if I could stand to come out here and live, and I have quite a few years.

JC: Of course we were married October 27, 1928, and moved down here permanent.

RM: What did you think when you made that first visit out here, Dorothy?

DC: Well, I wasn't very happy about it. I wasn't crazy about the place at all. I liked Las Vegas, but of course it's changed a great deal since then. It was a very small town in those days, but I became used to it and we've had a wonderful life.

RM: It was a big switch from Los Angeles, wasn't it?

DC: It was indeed.

JC: There were absolutely no conveniences. We had one faucet, running water in the house.

DC: Didn't even have an inside biffy for the first years, did we, dear.

JC: No electricity. You name it, we didn't have it. Except telegraph, which we do not have now.

RM: You had telegraph then because of the railroad.

DC: We have always had family in Los Angeles, and we spent quite a bit of time there. And we've had a wonderful life. I wouldn't change it, would you, dear?

JC: No. It has been perfect. There've been a few bad spots, but....

DC: I went to L.A. of course to have both of my sons.

JC: That was in the days when they went in a month before and stayed a month after.

DC: There weren't too many conveniences here.

JC: We had baths in the kitchen.

DC: In the washbowl.

JC: In the summer of course we had the shower.

RM: Did you heat water for the bath on the stove?

JC: In winter, yes. In summer we had a tank that got hot by sun.

RM: Did the water get pretty warm in the summer?

JC: Well, you couldn't stand it. Really warm. But we had our own water supply, our own well.

RM: There wasn't municipal water?

JC: Yes, there was. Reverts had a water system.

DC: The Reverts weren't here when we first came. I can't think what year they came.

JC: Well, the store was owned by E. E. Palmer, the big store, and they bought out Palmer.

RM: So there was a grocery store here in town at this time? Where was it located? Was it next to the Exchange?

JC: No, it was down across the street, down towards the river about a block. Quite a building.

DC: A big old building, yes.

JC: I think some of those pictures of mine will show it. But that was the center of everything.

RM: Was it also the post office?

JC: No, the post office used to be down the street, well that would be to the southwest.

DC: On Main Street.

JC: Palmer's was just the hub. It seems to me that the post office used to be there.

DC: I can't seem to think who ran the post office.

JC: It was Palmer's clerk—Thomas. And then later on it was Hob Dougherty, across the street and next door to the Exchange. It was there for years until it was moved up to the present location, and now they are moving it again. That, I think, is a mistake, but time will tell.

DC: Why are they doing that?

JC: I've seen that flood 2 or 3 times, just tear right through there. Jack has a lot of pictures of that flood; he was here. You could almost see the flood caning. Jack and I had gone to the mine, and there was about 6 inches of snow, 4-6 inches, and then it came, this heavy warm rain, which is just the makings of a flood.

RM: That was in '69, right?

JC: Roughly, yes. And then, Dot and I went to Vegas. I came down and told her we'd better go down, because things are really going to flood. Jack called me in Vegas the following morning and said, "Don't try to come home; there is no way you could get to Beatty." My sisters were alive at the time so we went to the coast and spent a day there, and then brought than back, and even then the roads were all closed. They had patrolmen stopping everybody. But we knew him, and he knew that we did live here. So he told us how to get here; it was to go down to the airport road and cross the river, and go over to Rhyolite and come in the back way, because you couldn't get through down at the narrows. It just tore everything out. RM: Did water get in your house here?

JC: No, it did not.

DC: We were lucky.

JC: Well, I often wonder why, because that's twice that I've seen it do that. One was in '23 when a flood come through, and we had several thousand feet of lumber stacked up in the yard out here. We never saw a trace of it. It just went clear through town.

RM: Did you find it downriver?

JC: Never found it, never found a piece of it.

RM: Isn't that amazing. And the lumber was right out here in your backyard?

DC: That's right. I remember trying to block it from coming into the house by setting 2 x 12s up on edge to try to turn the water, and I made it. The water didn't get in the house; it went clear through everything.

RM: Was that a summer flood?

JC: I think so, yes. Matter of fact, that picture that you saw, that rainbow, was from that flood.

RM: Have you had other major floods since you've been here?

DC: Not bad ones that I can remember.

JC: Those were the worst. But my father said the whole place was water at one time. From the railroad station on over to John Delf's ranch was all water.

RM: Down toward the south? From the railroad station, haw far down?

JC: No, across the valley, the Oasis Valley. I'm talking about right down here. There's a ranch of sorts down there now, but that was Delf's.

DC: I don't think anyone lives there now, do they?

JC: I don't know.

RM: Is it on this side of the narrows?

JC: Oh yes. There's a ranch over there that was owned by Delf in the old days, and then Bid Porter bought it. I don't know who owns it now.

RM: That was all under water?

JC: Dad saw it.

RM: So it sounds like every so often, they get a flood. The Amargosa drains a lot of country up there, doesn't it?

JC: Yes indeed. It all narrows down through there. You know that they call it the longest or largest underground river. But there's a lot of country up above that it drains.

RM: Dorothy, what was it like raising children in Beatty?

DC: Well, they never had a kindergarten here. They couldn't start school till they were 6 years old, you know, in 1st grade. It wasn't bad at all; we always had nice people here, and a few good friends. Of course we loved going back to L.A. whenever we could, didn't we, dear? I've never fallen in love with Beatty, as far as that goes, but we've had a good life.

JC: We took them down to L.A. every 6 months for a thorough physical.

RM: What did you do for health care here when the boys did get sick with the usual childhood things?

DC: Well, we were very lucky; they never got very sick.

RM: What did other people do? Was there a doctor in town?

JC: No.

DC: Went to Vegas. We were always down to Vegas-which was a 2-hour drive, in those days.

JC: It is now. It used to be one full day to get there by car.

DC: Oh, I don't remember that. That was before my time.

RM: On dirt roads?

JC: Dirt roads.

RM: A day to get down and a day to get back?

JC: Correct.

RM: And probably plenty of dust on the way.

JC: You get used to it. You never thought of dust--it was just there. You know it took us 3 days to drive into L.A.

RM: What route did you take to L.A.?

JC: Well, two. We could go north, go up through Oasis Valley and over the White Mountains over Westgard Pass into the Owens Valley. TO Owens Valley would take a day, a day over to Big Pine. Then it would take a day from Big Pine to Mojave, and then half a day from Mojave in. All dirt

RM: Wow, what a trip!

JC: On the other route you'd go to Vegas and then go down through ,Searchlight to Goffs, on the Santa Fe, which was west of Needles. Just cut off there 25 miles, and then turn west and go through Ludlow, Barstow and in that way.

RM Was that all dirt?

JC: All dirt roads. But we made it.

RM: Did you ever have problems with breaking down?

JC: Well I changed tires 27 times in one trip.

DC: We always drove Buicks in those days, didn't we, dear.

RM: You changed tires 27 times in one trip to L.A.?

JC: That's right.

RM: What did you fix flats with?

JC: That was the time when you didn't carry spares, as such. You carried the casing, and a tube, and when it went flat you took the tire completely off the clincher rims, completely off, and patched the tube, pumped it up by hand, and went on. This was a Ford. Then they talk about the good old days. Now you don't even carry a spare.

DC: What good old days!

RM: How often would you go to L.A. in those days, about the time you got married?

JC: Well, we liked to go in once every 6 weeks. And of course we tried to pay for it by bringing back a bunch of groceries. We always did fill the car up.

DC: We had both our sons; both of them were born near Los Angeles; our doctor was down there.

RM: So things were a lot cheaper in L.A.

JC: Yes.

DC: And better.

JC: Well you could get a better selection. You could get exactly what you wanted, where you couldn't here. You know we made-do.

RM: How often did you go to Las Vegas?

JC: Very seldom. Well, now, that's before you came out here, Dorothy. Now, when you came, well, let's see, the railroad went out in 1940. Of course that's when we had to go to trucking, and we trucked the spar [to Las Vegas] down and it it on the rails then. And the diesel, gas at first, and then diesel. We were on the road most every day, and we'd bring groceries back that way. And for a while we even brought gasoline back. Hauled everything. It was just economics.

RM: Did you ever have much occasion to go to Tonopah?

DC: Never have been up there very many times, really, have we.

RM: Were there churches in Beatty when you first arrived here, Dorothy?

DC: I'm trying to remember.

JC: We have never been church-goers.

DC: No, we haven't. We lead a Christian life, no doubt about that. N6, we're not great church-goers.

JC: Even though my grandfather was a Methodist minister, and her uncle was a minister.

DC: He was a Congregational minister for one year in a small town near San Bernardino; it was called Etiwanda. We lived in the house next door to the church. It was nice.

JC: In fact, he married us.

RM: Would you describe most of the people in Beatty as kind of like yourselves, not church-goers?

DC: I don't remember. Did our little boys go to Sunday school here in Beatty? I think they did. Of course I lived with my aunt and uncle in Etiwanda. I must confess I got a little tired of going to church 3 times a day. Sunday school, church, and then 7:00 in the evening, and I got a little tired of that. It probably did me good maybe.

RM: What other kinds of challenges did the isolation of Beatty present to you, in terms of living here, and working, and raising a family.

JC: I don't think we had any real problems. We didn't have any real sicknesses.

DC: We've been fairly healthy and we've been lucky that way. And we had a real good pediatrician for both our little boys in L.A., Dr. Victor Stork.

RM: Did you always maintain a residence in L.A.?

JC: My folks lived there.

DC: Yes, we were always very welcome to stay with them, weren't we, honey. They were wonderful to us.

JC: Then when he passed away, we stayed with my sister. And the same place that we go to now. She put that up in '39.

DC: We're so lucky. The homes are all on cliffs, and each house has its own stairway. We spend quite a bit of time down there. We're awfully lucky, and we appreciate it.

JC: We don't stay here all the time now.

DC: We've never fallen in love with the desert, have we, honey.

JC: No.

DC: I think that maybe Jack and Maudie enjoy it more than we.

JC: We were just stuck here.

DC: We've always had a few good friends here, but...

JC: But we spent a month touring Africa, a month touring the South Seas, and a month in the Orient.

DC: Yes, we've traveled quite a bit. When you live in Beatty, you need to.

RM: So you've traveled a lot.

JC: Yes. Oh, we've been up in Alaska, what, 4 times. I hunted there for a month.

RM: I notice you've got the trophies.

JC: No, not that one, the one on the other wall. Kodiak bears. Well, you see, Jack went into the service, and he put in for Kodiak.

DC: Both our sons were in the Navy. The younger son, too.

JC: Jack told us that he was putting in for Kodiak, because nobody wants that. So he did get it, and we made 2 trips up there to see him. We hunted one trip; then later on I went up with a friend of mine, Lorin Ronnow, and spent a month up there hunting. We like Alaska; and, as you've heard, we're figuring on our 23rd trip to the Hawaiian islands, fishing.

DC: You can tell we like Hawaii.

JC: It has everything the South Seas has, besides not so many bugs. Much better accommodations. So why go any other place. I can't catch the big fish anymore, but I always take....

DC: You've caught quite a few, dear.

Africa

Alaska

Amargosa River

Amargosa Valley, NV

Anderson, Mr.

Atomic Energy Commission (AEC)

bakery

Barstow, CA

Beatty, NV

Bethlehem Steel

Big Pine, CA

Bullfrog, NV

Bullfrog Goldfield Railroad

calcium fluoride

Cape Cod, MA

cement

Chicago, IL

Chloride Cliff

church

clay

Congregational minister

conveniences

Crowell, Annie L.

Crowell, J. Irving, Sr.

Crowell, J. Irving's sister

Crowell, Jack

Crowell, Maud-Kathrin

Crowell sons

Crowells' mine

Daisy Group mine claims

Delf, John

Depression

Devore

diesel truck

Dougherty, Hob

Drummond, Mr.

Durox Steel Co.

Eighty-five/five

electricity

Etiwanda, CA

Exchange

Fairbanks-Morse

Findley, Don

flat tires

flood

flotation

fluorspar

fluxing ore

Fontana, CA

galena

Goffs, CA

gold

Gold Center

Goldfield, NV

grey iron

groceries

hand augers

Hawaii

high-grade

hoist

horse and buggy

indoor plumbing

Italian

Japanese

Keane Wonder Mine

Kennedy, Bill

Kimball, Mr.

Kodiak, AK

Lafer, Sam

Las Vegas, NV

Las Vegas & Tonopah Railroad

leasers

Lige Harris

Los Angeles, CA

Ludlow, CA

McCall, L. S.

McDowell, Gertrude

McPherson, Al

medical care

Methodist minister

mills

mining

Mojave

Monolith (fluorspar buyer)

Mud Springs, NV

Needles, CA

Oasis Valley

Orient

Overbury Building

overburden

Owens Valley

Palmer, E. E.

Polytechnic High School

Porter, Bid

post office

Post Ranch

powder

Prince Edward Island

promoter

Pullman car

railroad accident

railroads

Revert family

Reverts' station, Rhyolite, NV

roads, dirt

rock plant

Ronnow, Lorin

San Bernardino, CA

San Diego Army/Navy-Academy

San Francisco, CA

Santa Fe Railroad

Sarcobatus Flat

school

Searchlight, NV

Seattle, WA

silica

South Seas

Southern Hotel

Stanford Univ.

steel

Stork, Victor (Dr.)

sulfide

Sunday

Swenerton, Arthur

teamster

telegraph

telephones

Thomas, Mt.

Tokyo

Tonapah, NV

Tonopah & Tidewater Railroad,

trucking business

U.S. Navy

U.S. Steel at San Francisco,

U.S. Steel at Torrance,

Univ. of Calif. at L.A.

Vidano, Louis

water

Westgard Pass

White Mountains

wire

World War II